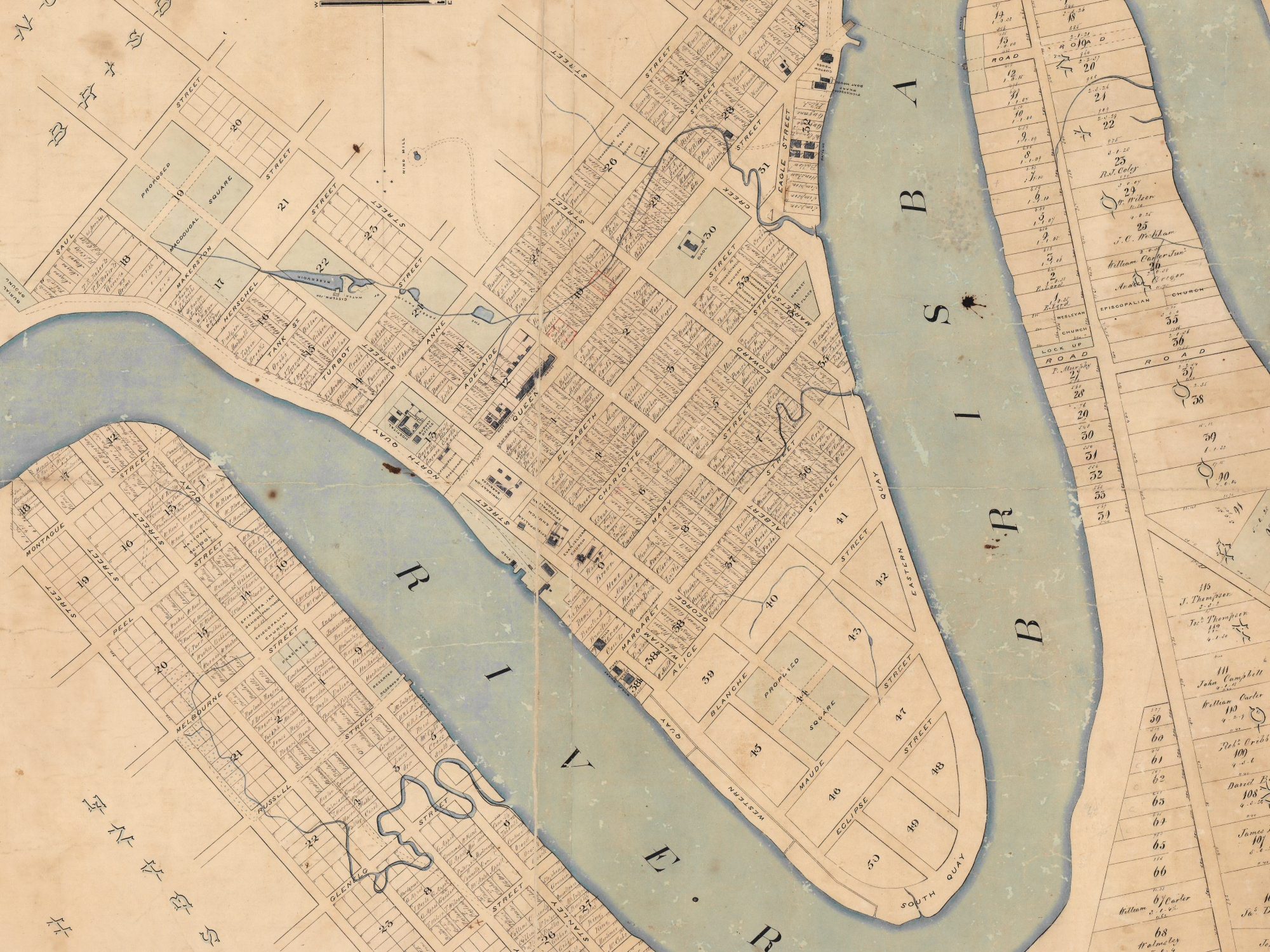

Meanjin, Brisbane, BNE. The River City lives upon the floodplain of the Maiwar, which for many millennia was a prodigious wetland. The Turrbal name of the locale, Meanjin (“spike”), refers to the pointed riverbend in which the central business district is nestled. The ghost of the swampland is still felt to this day, in the muggy depths of summer, the mangroves, the visitations of rainstorms.

This is a city defined by the river, born of the river, predicated on the river: there would be no Brisbane without the Maiwar. Its two ferry services, the CityCat and the KittyCat (“cat” being short for “catamaran”), are emblems of that originative yet embattled connection, as are the 17 bridges that stitch the city together across the meandering seam of the waterway.

The City of Brisbane began as a British colonial town. As with many such towns, it was erected where the water obliged to interface with the land, bringing cargo vessels to factories and financial centres. Constructed upon a river floodplain, the fledgling colonial city was named after Sir Thomas Brisbane, the governor of New South Wales at the time.

Once the place was named, its waterway was christened the Brisbane River—after the city it had sired, in a strange inversion of fates.

Before Brisbane’s founding in 1824, land and water bled into each other, smudging every sense of a boundary between them. Rain fell, then evaporated and suffused the air. Watering holes rose and receded. Earth and saltwater were stirred together into mud, breeding swamps, nurturing mangroves. Freshwater met saltwater where the Maiwar was fed by the stream that would come to be known as Wheat Creek.

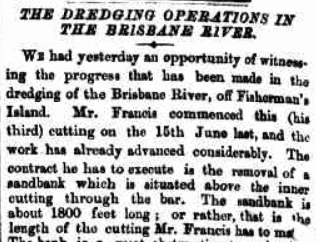

That view could not be sustained within a colonial paradigm of land, where a waterway is either a commercial channel or an obstruction. After the city of Brisbane came to be, its government set to work on the project of surgically separating land and river, using such instruments as dredgers and retaining walls.

Among the many alterations made to the geographical fabric of the region, the one that stands out is the complete erasure of Wheat Creek from the map. From 1863 to 1877, the creek was diverted underground into several culverts, making room for the street grid to be laid over its bed.

Even then—as Brisbane fed on quarried stone and sprouted ever larger—the land beneath its feet would always be a floodplain. The city, having now replaced its swamps and creeks with subterranean drains, satisfied themselves with the impression that they had vanquished the wetland.

But as they learned in 1896, there is no taming such a force of nature. Then, and always, the City of Brisbane would live at the mercy of the waters.

At the time of writing, we sit on the brink of another likely flood. Cyclone Alfred reaches our shores tomorrow (edit: now in two days’ time), and will bring a predicted 600mm of rain to shore. For context, the average annual rainfall here is 997mm: we will be receiving half a year’s worth of rain in a single day.

In 2022, during the last major flood in Brisbane, a low pressure trough sat over the region for a week, jettisoning almost 700mm of rain upon the city. This “rain bomb” coincided with the peak of COVID-19 in Queensland, approximately two months after the Australian government opened all state borders and discontinued lockdown measures.

I had a front row seat to the catastrophe, as the flood ravenously reconfigured a land ravaged by the pandemic: familiar streets reverting to creeks, waterfront commercial districts and bike paths going underwater, boats and bins and ferry platforms carrying hand sanitiser dispensers catapulted downstream in a frothing torrent.

It truly was the crossover event of 2022, a showstopping storm of isolation and devastation—where the pandemic had hollowed out the streets, the flood now erased them—a reality-bending one-two punch that alienated us from familiar places in one fell swoop.

Three years later, we are anticipating another such life-changing weather event. We’re waiting to see how many houses will total, how many businesses it will rub from the slate. It is like some devastating World Cup, keeping people across the state glued to their news feeds and weather radars.

I used to think I would see these kinds of events once a decade or so. But here we are. These days, it seems that the world only swings between flood and fire—that the turmoil is here to stay for good.

When I was 13 and learning the guzheng, my favourite piece was 占台风 (Zhan Tai Feng), or Battling the Typhoon. You can hear the etymological root of “typhoon” plainly in the Mandarin title, although the word is closer to the Cantonese pronunciation (“tai fung”).

At the time, I lived in a city that never saw tropical cyclones, because it sat in the intertropical convergence zone, where the gentle winds are unable to sustain a cyclone. So, for years, this guzheng piece was the closest affective link I had to those storms: sweeping and percussive, inspiring a terror so grand that it trickled down through cultural missives, secret premonitions, to people who had never seen them before.

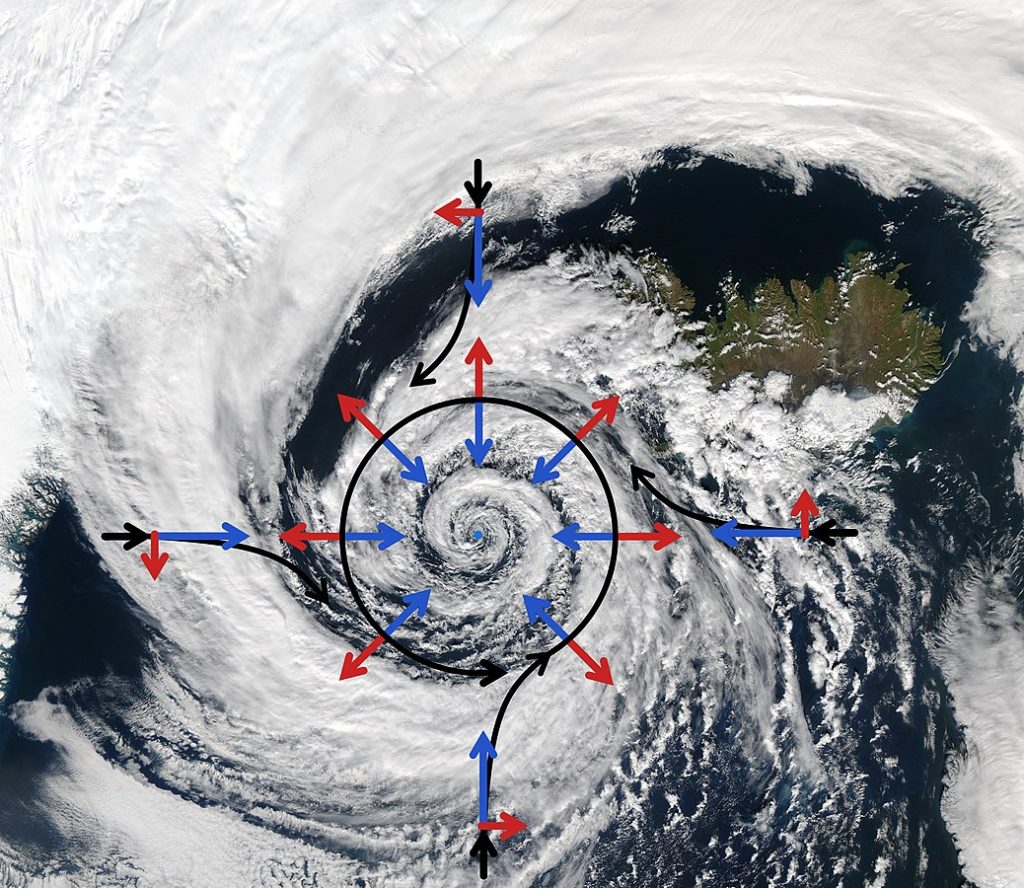

Here is where it is worth addressing the linguistic elephant in the room. Cyclones, hurricanes, typhoons all describe essentially the same phenomenon—rotating, high speed, low-pressure storms that arise over warm water—although “tropical cyclone” is meant to be an umbrella term for all of the above. Because “typhoon” is already established in Asia, and “hurricane” in Europe and North America, the term “cyclone” has come to refer primarily to the instances that arise in the Southern Hemisphere.

By that taxonomy, cyclones are distinguished from the other two by their direction of rotation: clockwise, whereas hurricanes and typhoons spin anticlockwise. The reason for this is the Coriolis effect: imagine rolling a wooden top between your palms, your left hand moving away from you, and your right towards you. If the top were the storm system, then your hands would be the northward and southward wind currents, deflected in different directions by the earth’s rotation and causing the air between them to spin. (In the Northern Hemisphere, you would reverse the directions of your left and right hands, producing an anticlockwise spin.)

Cyclones always develop at sea. The Coriolis effect, the rising of moist air, and the absence of land barriers all come together to concoct these thousand-kilometre-wide spinning tops of water and wind, blowing at 76km/h (34 knots) or more, which draw unfathomable volumes of water up into their bodies and carry them to shore.

Often, it is the winds that cause the most immediate and dramatic damage of any cyclone, batting loose objects about willy-nilly, felling trees, and tearing away stationary parts of buildings. But as we have learned, most soberingly through Hurricane Katrina, it is the floods they propagate that truly bring cities to their knees.

In Brisbane, almost every cyclone brings a flood. It’s not a question of if but when: we’ve already started to see flood risk maps for the coming storm, to add to the everyday flood awareness map that most Brisbanites already know well.

It is thanks in part, again, to the Coriolis effect and the ocean gyres that circulate warm water from the equator towards the poles that east coasts of continents tend to be more humid than their west coast counterparts. In humid subtropical climes, summers are especially wet, and coastal wetlands abound, and the warm evaporating water fuels stormclouds.

When colonial city planners drained and filled the wetlands and replaced them with roads and buildings, they effectively eradicated its natural drainage system. And well, the rest is history—history with a death toll of a few hundred.

It was Cyclone Wanda that brought upon the region the floods of 1974, killing about 30 people, flooding 6,700 homes, wrecking a ship, and washing away several bridges. After that flood, and another in 2011 which washed the riverfront boardwalk away, the city had to learn fast.

The ferry terminals became the site where that learning was most visibly tested. Damaged during the flood, they were replaced with a brand new design, shaped like hydrofoils facing against the current with bridges that could detach from shore to prevent a buildup of debris. These new terminals were designed not to withstand strain, but to float and sink and untether themselves as needed. Come the 2022 floods, they were put to the test—and luckily for them, they passed with flying colours.

These engineering successes stood as a testament to the prevailing understanding of flood engineering, and perhaps of climate response as a whole: there is no triumphing over the rising tides.

East-facing coastal cities are like a climatic petri dish, revealing that the illusion of human dominion over nature is easily wiped out by a slight tipping of the biosphere. Some of these tilts may be naturally occurring. Others may be the consequences of our own short-sighted efforts to master the world.

Either way, when the waters rise, we cannot goad them into retreat—only try to stay afloat.

In Australia, cyclones are named alphabetically in order of identification. The list runs cyclically from A through Z, alternating between masculine and feminine names.

These names are an instrument of standardisation and clarity: they are agreed upon among neighbouring countries to ensure continuity in news coverage and to avoid ambiguity when discussing concurrent cyclone events.

More than that, however, the names aim to raise awareness of cyclones—to generate the interest, respect and terror that they warrant by investing them with anthropomorphic identities. This is why, when a cyclone is especially destructive, its name is never used again: forever will it be the name of that cyclone, embedded in the cultural consciousness, as christened, for perhaps the rest of history to come.

In a way, we are being asked to see storms as beings—deities, perhaps—with identities rendered in how efficiently they tear through our cities. Cyclones are capricious creatures—rapidly changing paths, forcing meteorologists to revise their projections every few hours.

It is also in the essential nature of such deities to destroy without thought nor reason. After all, a storm is called a cyclone on the basis of its destructive wind speed. There is no cyclone that is not capable of devastation: that is the sole and inexorable reason we name them.

Our cities have names, too—but they tend to have many, a different one for each of their faces. Meanjin harkens to the river, which has snaked through Turrbal Country before the street grid was a figment of imagination. Brisbane is the colonial city, taken from Thomas Brisbane, like a child descended from a father.

To the pilot, she is BNE or YBBN. To the postal service, he is 4000. All of these epithets, familiar or alien, give us ways of distinguishing this net of roads from every other.

But when the many arms of the cyclone spiral over our city, all of this will grind to a halt. Planes will be grounded. Roads will be empty. Letters will be held until it is safe to drive again. The river will rise, and rise, and maybe take shards of the metropolis with it. Only the satellites will blink on, watching from above as our city is battered by the wings of the storm.

Not the city, but our city: it is not just an agglomeration of steel, concrete, and capital. It is the roads we walk, the friends in other buildings, the cell towers beaming snippets of our lives back and forth. That’s why it is so frightening to watch roads go under, to wait for the power to drop out, to hear the tally of destruction at the end. It is our place, our selves, even, that come unmoored when the world turns over.

As I watch from the eve of the first cyclone of my life, Brisbane City is abuzz with nerves. Supermarkets have been raided clean of food and lighting supplies. Schools are closing. The city ferries have been put away. Power outages are already beginning to be reported.

I have a 2-litre jug of water in the fridge, ready to go should the supply of water be disrupted. Today, I bought a candle and learned to use a cigarette lighter, and I am charging my devices one by one.

Once again, and ever more, the earth behooves us to notice how precarious the networks enmeshing our lives really are. There is no light, no water, no conversation without the systems we’re strung into—traffic, plumbing, power grid, postal service, internet, economy, climate. Alfred will be the first cyclone to hit Meanjin in 50 years, and damn, do I hope we’ve learned something in that intervening time.

Leave a Reply