(Post 3 in my 2024 Travelogue)

Oh, Hong Kong, how do I write about you?

I’m brimming with gratitude that I had the chance to visit after wanting to for years. But can’t help a sort of grief too, at the signs I saw at every turn that the city was changing for good.

I did not intend to be a voyeur to this, but maybe that can’t be helped when one is dropping into a country for a week and then leaving without a trace. I have only glimpsed a fragment of the universe housed within its seams. But here’s what I saw this time.

Preface

The day I landed in Hong Kong, 47 activists were convicted of “interfering” with the previous election under the National Security Law instated in 2020. They had already been in jail for four years, but many will be in jail for years more. I don’t have the knowledge and familiarity to write about it opinionatedly, but it set the tone.

The real reason I have wanted to visit Hong Kong is pretty shallow: a few future chapters of my web novel are going to be set there. I have had this chapter planned since 2018 or so, and it’s been a place of fascination to me for about that long; I once did a study of a photo taken from Victoria Peak:

But over time, the number of reasons I had for visiting grew. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, I joined a share house with a roommate from Hong Kong. In the depths of those ruthless Australian lockdowns, where everyone in that house had nowhere else to go, Nathan catalysed all social interaction there, pulling us together as a tiny community. In the year between when we met and when he went home, we had numerous hotpot dinners, tried fancy cheeses and wine together, and drank in the backyard under the stars—all little rituals that turned that part of my life from amorphously bland to unforgettable.

Nathan returned home in the middle of the pandemic, shortly after the new laws were passed in his home country. I began my PhD research, which looks at how cities emerge as interconnected ecosystems of people, with each other and with the physical structure of their cohabited space—encoded in habits, memory, movement, and history.

I love places. I love how much the shape of the geography can tell one. The angles at which roads intersect, the languages on signs, the colours of lamps… You can read the streets like a book, layers of change and history encoded in them… And when I finally went to Hong Kong, all of this came to the fore, and more.

I know that many like to know what stands out about their country to an outsider, so let me start there.

Victoria Harbour

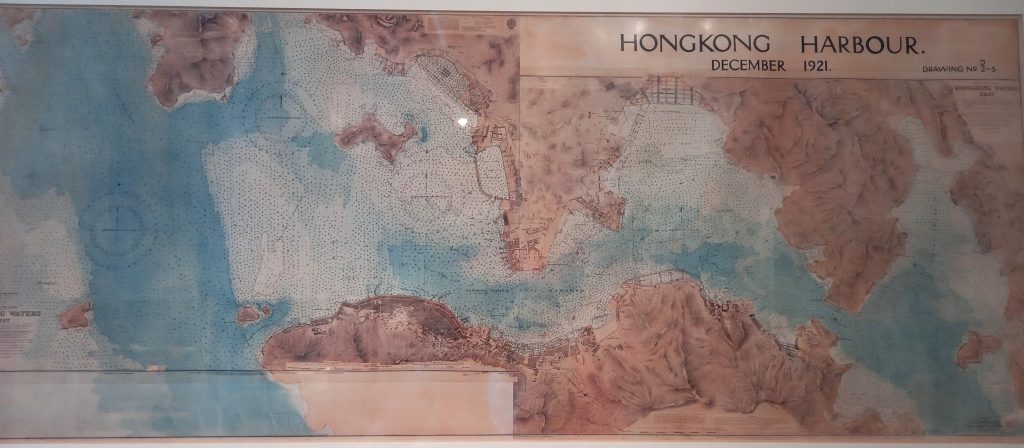

It’s in the name: Hong Kong, 香港, translates to “fragrant harbour.” The city-state’s tourist branding heavily features the Chinese junk—a sailboat that saw its heyday well before the advent of steam. At once, it symbolises the city’s roots as an ancient seaport, and its modern economy’s continuing reliance on sea trade, while also representing one of its tourist attractions: a fleet of boats built in the historic style, touring the harbour daily.

I’m a huge enthusiast of all things maritime. I grew up close to a port. I watch videos about container ship mooring teams and port design in my free time. So, you won’t be surprised to know that sitting between two skylines, each in full view of the other’s shore, watching civil ferries, tourist vessels, and container ships course along the waterway…made me a little emotional.

Victoria Harbour—the strait that runs between Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon peninsula—is a waterway with a hundred volumes’ worth of history. So foundational has it been to the trade of the region, and for so many centuries, that its name well precedes it.

But it’s one thing to know that from reading, and another to see it with one’s own eyes.

From the day I laid eyes upon the harbour, I was enamoured of it. I returned almost every day, viewing it from various angles, crossing it via every available mode of transport, and taking entirely too many photos.

There are pedestrian walkways spanning both coasts (that’s the urban developers going, “Stroll and linger and behold the harbour! Isn’t it grand?” —and it is), so I walked along each shore, sometimes sitting to draw the scenery with freezing hands. My Octopus card let me onto the cross-harbour Star Ferry, so I took that, too.

There is a Maritime Museum on Hong Kong Island that pays homage to the role of the sea in shaping this city. Through peace and war, prosperity and strife, from the omnipresent humidity to the names of its neighbourhoods, from container ports to sailing regattas—it’s a port city, and you can’t be there without knowing it.

Is there anything more breathtaking?

Parallel pasts

It’s hard to articulate exactly how, but there was something…subtly comfortable about being in Hong Kong. There was no culture shock; I did not have to think about changing my behaviour to match local etiquette, because my natural manners seemed to fit in.

It was the first time I became aware of my skill of navigating crowds with an umbrella—one I had acquired at home, and now served me well again after years of irrelevance. I had never felt like such an expert in something so mundane before!

What startled me perhaps the most was how intuitive the transit network was to use. In fact, it was so natural that I could almost immediately put Google Maps aside and start to navigate improvisationally. The MTR network simply is that well designed and tightly maintained: trains arrive every few minutes, do not randomly skip stops, and stations are overflowing with maps. Nathan tells me there isn’t much need for people to learn to drive, thanks to the reliability of the transit network. And I could see how.

Perhaps as a holdover of Hong Kong’s history as a British colony when the power grid was installed, its power sockets follow the UK standard. Australia, despite still having the King of England as its head of state, has its own plug. I, with my stash of plugs and chargers from Singapore, have been attaching them to Australian sockets with adapters for years.

So, it’s funny to think that this was my first vacation ever where I didn’t need to bring a power adapter. Thanks to a certain colonial power that went rampant across the world two centuries ago, all my plugs fit straight into the sockets here.

In my youth, I knew a thing or two about our relations with Hong Kong. Just like I grew up with classmates and teachers from there, I was surprised at the number of Singaporeans and their businesses here. I must not have realised how much reciprocal flow of people there has been, or how deep that history runs. Perhaps it comes with the territory of being two East Asian seaports since time immemorial?

The cherry on top was finding out that my high school was running a reunion event here…the day after I left. (Alas.)

Neighbourhoods

In Hong Kong, there are many streets and shops with no names. This stands at odds with the paradigm of the world that has settled well into my mind—one where everything is labelled and searchable.

As outlined in excruciating detail in a previous post, I like to move without a destination. I set aside a couple of days to play my favourite navigational game—picking a random neighbourhood MTR stop and going there to see what I would find.

There was a world of difference between the commercial districts (like Tsim Sha Tsui) and the ones farther from the financial centre (like Sam Shui Po), from the age of the buildings, to the level of maintenance, to the kinds of retail and food available. This doesn’t surprise me; I suppose it’s in the nature of a city with a major part of its economy reliant on tourism—you could distinctly sense that some places were built to be “front-facing”—for tourists, while others serve the pragmatic needs of the people of the heartlands.

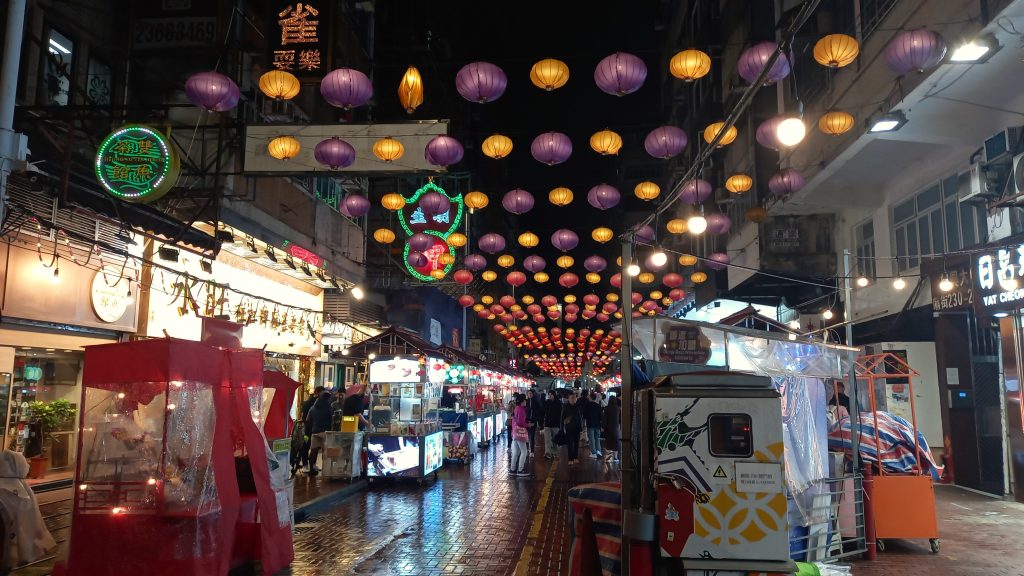

Here in Hong Kong, shops are—more often than not—open well after dark. I was never out of options, where I would have been in Brisbane. This is not something that comes easy, as I’ve learned: it takes a culture that sees work as virtuous and rest as somewhat worth sacrificing, for shops to be open so far past office hours. Most of Brisbane becomes a ghost town by 9pm. At 9pm, the streets where I stayed were still bustling.

In most of corners I went, I found wet markets, night markets, malls and claw machines. The last of those especially surprised me: there were entire villages of them, crammed back to back into winding alleys inside shopping malls. Curious, I read and learned that these shops started to crop up in the past few years as the economy has receded, that they are all very rigged, and that this is perfectly legal.

Some shops were family run, and others were corporatised chains, all sharing streets and complexes. Some, I’ve forgotten the names of. Others did not declare their names at all. There was something I liked about lurking in those nameless places, and—briefly—seeing life from within.

Languages

I went to Hong Kong more or less assuming that I would figure things out between English, conversational Mandarin, and my ability to read Chinese. My efforts at learning Cantonese were a little lacklustre (I know how to count, say thank you, and apologise), so I knew my vocabulary would not help me beyond touch-and-go shop transactions.

In reality, I think I would have survived just knowing English…but being able to read Chinese saved me heaps of time and frustration.

Really, the city is effectively trilingual. I only met two people whose sole spoken language was Cantonese (both were older people). Almost everyone else also spoke either English or Mandarin, if not both. Most signage was given in two written scripts—English and Traditional Chinese—and MTR announcements were in all three.

Having observed this, I do wonder what the standard is for language education in schools. Do students learn all three languages? Has this changed recently?

Whatever the case…the next time I visit, I will probably learn more than just Cantonese numbers and greetings.

Three years older

Meeting Nathan again was, from the first, surreal. This was a face I had not seen in three years, yet I knew him the instant I saw him, approaching from a distance. We kicked off with a HK $300 hotpot in a central neighbourhood, then roamed an old shop of luxury goods, looking at jade trinkets and calligraphy tools neither of us would ever buy.

We met up a few days later for ramen, then climbed the hills in Soho and bought a lottery ticket (no wins). He showed me his favourite bookstore, where we sat and read for a while. I read a book of academic essays about community arts in Hong Kong, but it was about a Hong Kong different from the current one.

At every turn, there was a sense of the world turning, the streets changing. The neighbourhood—once a crowded tourist destination, he said—was much emptier than it had once been. His bookstore was struggling to stay afloat, and he feared it might not last long.

I, of course, would only be here for a week, and then I would pack up and leave, having taken the beauty and joy this place had to offer, and none of its troubles. That future was not mine to worry about.

But it was his, and it has shaped his hopes and plans. Plans that may take him far away. He wants to leave for Europe. It would make meeting harder.

I don’t think I caught the name of that bookstore—maybe I should have. We took the MTR back to Tsim Sha Tsui, and parted ways at the train doors. He had work the next day—a Sunday.

Such is a friendship so singular and unlikely, and so tossed about by the changing circumstances of the world. The premise of our friendship has always been the awareness that any parting may be our last.

Will we meet again, in this city or another? I would like to hope so.

Leave a Reply